“When it comes to me, I set the bar pretty high,” Honors student, Helen Gooding said.

Gooding, now in her early 30s, has earned three associate degrees and three professional certifications. Each time, she graduated at the top of her class. She works full time and has two school-aged children at home.

“I don’t give up,” Gooding said.

Her story is as unique as it is familiar for many of the non-traditional students who work full-time, carry a full load and take care of their kids. It is an undertaking that requires nerve, resilience and an abiding comfort with stress.

“My upbringing outshines my situation and brings me through it.” She was raised by a single mother of three. She was the one who “was usually the problem child when it came to health concerns for [her] mom,” Gooding said.

“I was in the ER probably a dozen times before I turned two, a handful of times I was put in the oxygen tank for pneumonia or asthmatic related issues,” Gooding said. “I was always the one who stepped into the wasp nest and got stung fifty times, stepped on a piece of glass, climbed a tree and broke a wrist.”

While her mother was caring for her and her two older siblings, her mother completed her BS in Physics with honors at UC Irvine in southern California. Now remarried and retired in Oklahoma, Gooding’s mother managed to find a highly successful career working for an international aerospace firm.

“It was the example my mom set that sets the standard for me,” Gooding said.

In an alternate version of her life, Gooding might not be working on her Bachelor’s Degree or living in an apartment with two children. For most of her youth, she dreamt of being a pilot in the Air Force.

The teenage Gooding, gifted in fine art skills, was selected to enroll in an exclusive art school in the Midwest. She also can imagine herself being a doctor with a practice on the coast of the Pacific Ocean. However, something happened that kept her from going in any of those directions.

” Even with all my accomplishments, I still need to get this degree so I can get out of poverty.”

Helen Gooding

“I became epileptic. I started having seizures when I was 16,” she said.

In the beginning, she did not tell her mother about them.

“I did not want her to think I was taking drugs or something,” Gooding said.

In high school, Gooding was a competitive, fast-pitch softball player. Some members of her team mocked her seizures and laughed at her as she came back into focus. She said, “It was hurtful. It was bullying.”

The seizures became more frequent and intense. She graduated from high school without having a working diagnosis or treatment plan.

She started college, working on what would be the first of her three Associate’s Degrees. Gooding had a seizure while driving. The result was a collision that nearly killed her. She said the near-death experience is always with her, nearly 16 years later. “You can die in a moment. Anyone can,” Gooding said.

At the point in time when she had the accident, she was having as many as 25 seizures a day, despite all the medicines she was prescribed.

Her nature allowed her to risk blindness, deafness and even death to undergo brain surgery that might end her seizures. The surgery removed half of her hippocampus, which is a part of the brain that encodes long term emotional and spatial memory.

“I have been seizure-free for fifteen and a half years,” Gooding said.

After her surgery, she returned to community college and graduated on the honor roll. “I have to study ten-times harder than the average student. When in a conversation, I can sometimes forget where I am going,” she said.

The surgery definitely has affected Gooding. She said, “I need a lot of reminders. I make a lot of lists. It is that much harder for me because I am missing that part of my brain.”

Thirteen years ago, Gooding got married. He was active duty Army. Eventually, he was discharged with disabilities.

“I was a single parent ever since my daughter was born,” Gooding said.

With money tight from her husband’s discharge from the military, Gooding said she “had to become an active breadwinner.”

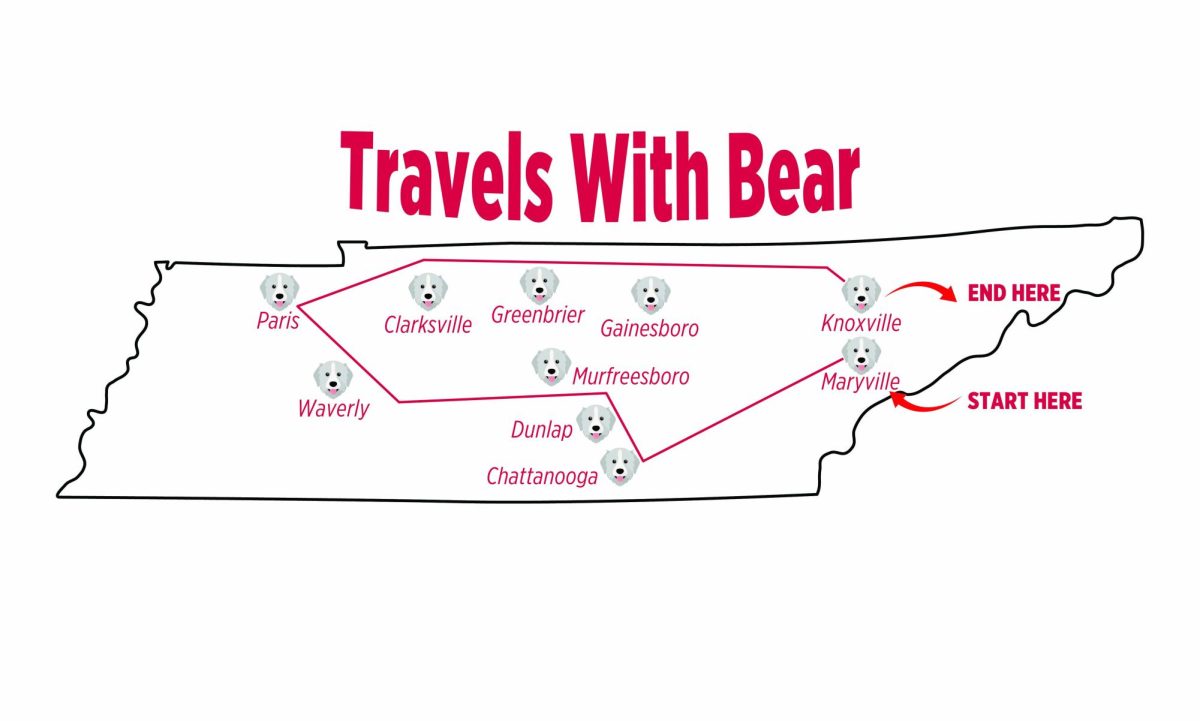

Gooding recently divorced, explaining that the marriage was “just too much stress.” This April, she relocated from across the Kentucky border and got an apartment in Clarksville. She is the primary parent to her six-year-old son and eight-year-old daughter.

Meanwhile, she takes a full-load at the Education Center at Fort Campbell two nights a week.

“It is Microbiology for five hours each night and an online class that fulfills my minor,” Gooding said.

Gooding works full-time, four days a week as a dental surgical assistant. Any free time is spent with her children, taking them to family nights at school and back-and-forth between friend’s homes.

She has a good friend from church who looks after her children while she takes night classes at Fort Campbell. Her friend does not charge her for the service.

Early and after school care costs being high, childcare consumes a big chunk of what she is able to bring home. But the alternative “would be living on welfare, having the government pay my bills.” That is not an option for Gooding.

When taking a personal inventory, Gooding ticks off a few of her distinguishing characteristics: She is a thrill-seeker, expressive and artistic, a tough self-critic, ambitious and visionary. “20/20 eyesight is all I have going for me,” she joked.

Based on that self-assessment, it is no surprise Gooding is not a fan of less than stellar performance.

“If I get a “B” on something, I feel like I could have done better and wonder what I could do differently. I know the “A” is a possibility, so why not?” Gooding said.

Gooding is a scholarship student. Having knocked out a few prerequisites this summer, this month she hopes to be accepted into APSU’s nursing program.

“I see myself as a nurse for sure, that is what I am visualizing right now,” Gooding said.

If accepted, that will mean rearranging her schedule and practically her entire life. Full-time on the Clarksville campus means renegotiating the job situation and childcare, but it is what she is focused on right now.

”I am doing this for my children so that we don’t have to live on welfare and only have the minimum. There is more to life than just living day-to-day. If you put your effort out you can see how many great things there are. I want to teach my kids not to give up,” Gooding said.

Gooding shared a closing perspective that was a bit unnerving. “This country does not value education in a way that helps me and my family. I have spent enough time in school to be a doctor by now. But, even with all my accomplishments, I still need to get this degree so I can get out of poverty.”

The way she sees things, everyone deserves access to food, affordable housing, healthcare and a good education. But for her, she feels the need to earn her shot.

“I can’t recall a recent time without a lot of stress,” Gooding said. “I think stress makes me perform better. I never give up.”