Under the shadow of the opioid crisis, APSU finds new ways to help protect students and the community.

Campus police have established a secure drop-off box for the safe disposal of prescription medications.

“One of our officers came up with the idea. He knew of this program and he asked us if we would be willing to do this,” Campus Police Chief Michael Kasitz said. “So, this was an initiative by one of our patrol officers, Euman, to try to keep prescription drugs out of the hands of people that shouldn’t have them and to keep them from going in our waterways.”

The opioid crisis or epidemic is defined as the rapid increase in the use of prescription and non-prescription opioid drugs in the United States and Canada starting in the late 1990s and continuing throughout the next two decades.

Opioids are natural or synthetic chemicals that interact with opioid receptors on nerve cells in the body and brain and reduce the intensity of pain signals and feelings of pain. This class of drug includes not just prescription pain medications such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine and many others but also includes the illegal drug heroin and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.

Opioid pain medications are generally safe when taken for a short time and as prescribed by a doctor, but because they produce euphoria in addition to pain relief, they can be misused.

Due to their sedative effect on the part of the brain that regulates breathing, if taken in high doses, opioids present the potential to cause respiratory failure and death.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2018 Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks, more than 191 million opioid prescriptions were dispensed to American patients in 2017 with wide variation across states, Alabama is the highest prescribing state wrote almost three times as many of these prescriptions as the lowest prescribing state Hawaii.

Additionally, the report noted that in 2017, Tennessee had the third-highest opioid prescribing rate of all fifty states with 94.4 prescriptions per 100 persons. Tennessee was also the third highest extended-release, long-acting (ER/LA) opioid prescriber with 8.7 prescriptions per 100 persons.

“I see this program growing because a lot of people in our community need this type of service,” Kasitz said.

Trey Chrystak | The All State

In response to the prevalence of these drugs and the dangers of misuse, secure, authorized drop-off locations are appearing across the country so that Americans can safely dispose of their unused prescription medications.

“Many people have leftover prescription drugs that they don’t use and then it’s how do you dispose of those? The thinking in the past was people would flush them down the toilet so no one else would take them, but that pollutes our waterways and causes other issues,” Kasitz said.

Despite this, the Federal Food and Drug Administration does have a “flush list” or list of medicines recommended for disposal by flushing when take-back options are not readily available. OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin and Diastat are among other medicines included on this list. These medicines may be especially harmful and, in some cases, fatal with just one dose if they are used by someone other than the person for whom they were prescribed.

The FDA has expressed the belief that this risk outweighs the risk to human health or the environment that could be posed by flushing these drugs, therefore necessitating their immediate expulsion from the home via a toilet or sink.

The full “flush list” can be accessed at the FDA’s website: fda.gov

“There’s really very few safe ways to dispose of prescription medications. So, we partnered with the state to get one of these take-back boxes so that people could come to our location and safely drop off the medications to have them destroyed by us later on in the appropriate way,” Kasitz said. “Most of the time its incineration. So, we’ll partner with the hospital or the Clarksville police department who have an incinerator and we’ll make sure it’s done in the proper way.”

For drugs not included on the “flush list” in instances where take-back options are not available, the appropriate disposable process, accoridng to the FDA, includes putting unused prescription medications in an unpalatable substance, such as kitty litter, coffee grounds or dirt which is placed in a container such as a sealed plastic bag and then thrown in the trash. Personal information should be scratched out of the labels of prescription bottles before disposal.

Additionally, it is important to note that tablets and capsules should not be broken before disposal as contact through the skin or by inhalation of the dust could be potentially harmful to all household members.

Prescription drug abuse is a prevalent problem throughout the country affecting even our region and community.

The CDC stated that in 2016, by region, age-adjusted death rates for drug overdoses involving prescription opioids were highest in the South with 5.8 persons dying from drug overdoses involving prescription opioids per 100,000 people.

The report also noted in 2016, rates of drug overdose deaths ranged from 6.4 per 100,000 in Nebraska to 52.0 in West Virginia in 2016. Kentucky was also among the five states with the highest death rates of drug overdose death with 33.5 per 100,000.

With this being such a prevalent problem, the issue of proper prescription drug disposal becomes even more pressing, and even with the other methods of disposal described by the FDA, there is only one that is appropriate for all prescription drug disposal: medicine take-back options.

Medicine take-back options such as permanent drop-off boxes are available in local law-enforcement facilities, hospitals and even retail pharmacies, such as Walgreens.

“I’ve noticed a lot of bins at Walgreens. In fact, I’ve seen on multiple occasions the Walgreens on Madison Street is fully filled. So, they have to close it up until it gets emptied. Based on that, I’d say there’s good response on people getting rid of that stuff,” Bill Persinger, Director of Public Relations and Marketing said.

The process to obtain the drop-off box was initiated two years ago and was fully realized at the end of last semester. However, with the start of winter break looming, they decided to postpone the announcement until the beginning of the spring semester.

Kasitz believes having this drop-off point on campus is a benefit to the entire community, stating that he has already received support.

“We just sent out the one mass email and we put it on social media. So, we’ve tried to hit people, and I got instant reactions. I got emails back almost immediately from people who’ve had the experience of wanting to get rid of old prescription medications but had nowhere to go,” Kasitz said.

Items accepted in the new drop-off box include prescriptions, liquid medications (in leak-proof containers), medicated ointment, lotions or drops, pills in any packaging (glass bottles, plastic containers, plastic bags,) over-the-counter medications and pet medications.

Items not accepted include blood sugar equipment, sharps/needles, illegal drugs & narcotics, thermometers, IV bags, bloody or infectious waste and personal care products (shampoo, lotions, etc.).

“I just hope that people learn that we have this and know they can come in at any time. We’re open 24/7,” Kasitz said.

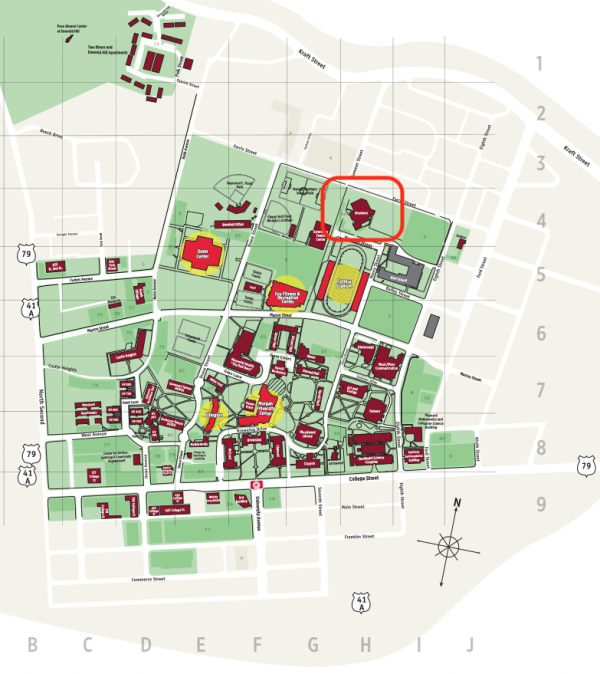

The prescription take-back box is located in the Shasteen Building.